The Oldest Pilot In IRAQ

Jack Sharkey was supposed to retire at 60, but when his National Guard pals were called to Iraq, he had to go too

By .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

E-mail this story | Print this page | Archive | RSS

With Hawaii National Guard colleagues and

a Chinook in Iraq

His friend, Chief Warrant Officer Oliver R. Kalop, calls him a hero. Maybe it’s his distinguished service cross and 26 air medals.

Or maybe it’s because when Jack Sharkey faced mandatory retirement two years ago at the age of 60, he petitioned the Army for more work time. He wasn’t about to let his friends and colleagues in the Hawaii National Guard face their most difficult task alone. So at the age of 61, Sharkey became possibly, most likely, the oldest pilot in Iraq. In fact he was probably the oldest U.S. serviceman in the entire country.

“There are probably a lot of reasons,” says the Chinook helicopter pilot. “I guess it’s just the idea of not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for it. I guess it was just the way I grew up. Plus when you’ve been with these guys for over 20 years, you make a lot of close friends, and if you’re in a military unit you don’t want to see them go somewhere without you. Even though I was old I felt I could still do the job.”

Sharkey’s military career began after he was commissioned a Marine officer in 1965. Three years later he was in Vietnam. After a year running with ground forces while helping to coordinate air strikes, he volunteered for another go-round.

“That was the first time I volunteered. I guess I’m a pretty slow learner,” he said as he laughed at the thought. “I just wanted to go back and fly more after that time on the ground. I felt some of my friends were getting ahead of me in air missions. And when I was with the grunts I saw they needed a lot of help, and being on that side of it I felt like I could do that again.”

After a seven-and-a-half year stint, Sharkey left the Marines and got started on his job with Aloha Airlines. That gig lasted 30 years. Soon after the former New Yorker, born in Queens, married local girl and Roosevelt High School grad Kathleen Ing. “I never forget the date because it’s on the Marine Corps birthday,” he confesses. Four children followed, one of whom is keeping the family tradition alive. Daughter Malia is an Air Force airfield operations officer in Shreveport, La. She is also doing the waiver thing in trying to enter flight school. She’s a bit on the short side.

Sharkey joined the National Guard in 1980 when he heard the unit was looking for pilots. Feeling the need to again serve his country, he began training to become a helicopter pilot. It was not a completely simple transition, he explains, because of the different skills required. But once he got the hang of it, it became something he loved to do. And the benefits weren’t bad.

“We flew these little scout helicopters,” he says. “We did a lot of green harvest missions (marijuana eradication) when it first started. I saw some beautiful scenery way up in the mountains that you would not be able to see without a helicopter.”

With the buildup to war in Iraq, Sharkey knew it was only a matter of time before the men and woman at Wheeler Army Airfield would get the call. The new transport helicopters made the unit very valuable to the Army. He got the OK from the government, but forgot to talk to the commander who really matters, Mrs. Sharkey.

“I must confess that I never asked my wife,” he says. “You’re supposed to be a team and discuss all this stuff, but I decided I have to do this. I just came home and said I wanted to extend and she said OK. She never said boo to anything about what I wanted to do in my career.”

Even with family support, deployment can be a hard thing. Especially on those left at home. “She’s been very supportive the whole time,” he says. “I owe her a lot because it was very trying for her. She stressed out a lot. Before I went she was trying to hide it from me because she didn’t want me to worry about her when I was over there.”

Once the 200-plus members of the Charlie Company 193rd Aviation Heavy Helicopter got the call, it was things as usual for the over-achieving unit.

“We thought we were behind, but when we got over there we found the other units weren’t nearly as qualified as we were,” Sharkey says.

That ability to get things done initially surprised area commanders when insurgent activity called for the quick movement of men and machinery. The Wheeler crew got their entire fleet from Kuwait to Balad, Iraq, overnight — something no other unit did. Other major accomplishments were flying more than 31,000 hours at night, giving Saddam Hussein a lift (no one will say where he was or where we went), taking home former Iraq administrator Paul Bremer, and supporting Iraqi police, army and international forces. Pretty nasty duty when you consider an Army study found the outside temperature of the aircraft was 115 degrees at 1 a.m. During the day, those temps rose to 140.

“Most units don’t have enough people to fly all of their airplanes under goggle (at night) conditions,” he explains. “The active duty unit that replaced us had hardly anybody. Their proficiency and experience level was far lower than ours. They had hardly anyone that was night-vision qualified.”

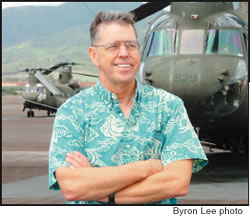

Jack Sharkey, back home at Wheeler

Upon meeting Sharkey, you wouldn’t expect much of a thrill seeker. He moves around the airfield, exchanging handshakes and greetings with anyone who crosses his path. The military standard of using last names only is something Jack has never abided by. Whether young or old and no matter the rank, it’s all friendly banter with first names only. No doubt his ability to relate to those around him was a great help when things got testy in Iraq.

And they did.

“Sometimes some bad things did happen. How intense it was varies with who you talk to,” he says. “I can tell you a lot of people went over there who had never been into that kind of situation before, and they were pretty nervous.”

Flying at night, low and fast, is a hard thing to do for an experienced air crew. For those on their first deployment it’s even tougher.

“They saw threats everywhere, especially initially. When you’re flying at night with goggles on,

Page 1 of 2 pages for this story 1 2 >

E-mail this story | Print this page | Comments (0) | Archive | RSS

Most Recent Comment(s):