Marching Home Again

They returned from war without any injuries, but these four men who served in Iraq and Afghanistan will never be the same

Derek Chow, a Civil Works project manager from the

Honolulu Engineer District, interrupts an Al Nidhamniya

School class for a construction inspection. Chow served

four months at Forward Operating Base Danger near Tikrit

Since the start of Operation Enduring Freedom shortly after Sept. 11, 2001, and throughout Operation Iraqi Freedom, which began March 2003, thousands of Hawaii-based troops have been deployed to those war zones. Here are the stories of some of those who came marching home again.

Capt. Gavin Tsuda, 35 Hawaii Army National Guard 2nd Battalion, 299th Infantry, 29th Brigade Combat Team Baghdad, Iraq

“My friend told me before I left that once you deploy, you go to war and you come back, you can live the rest of your life knowing you made your contribution to society,” says Capt. Gavin Tsuda, a citizen soldier with the 29th Brigade Combat Team. “Not to say your job is done, but you did your part. I like to think I did my part.”

For almost a year in Iraq, Tsuda, a bronze star medal recipient, did his part. He remembers crossing the Iraqi border from Kuwait on Valentine’s Day 2005, and watching the terrain change in the three days it took to get to Baghdad. It was like a scene from Mad Max, as his convoy of trucks and armor-plated vehicles traveled first through the flat, uninterrupted desert and continued past an occasional camel, scattered homes and people he believes were Bedouins.

In Iraq, Tsuda could go months working 15-, 16-hour days without a day off, but even then, he says, “We had a lot to do, I could never catch up.” When he returned home to his wife, Cheryl, and their son Kenji three weeks ago, he was 20 pounds lighter than when he left.

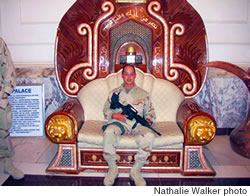

Capt. Gavin Tsuda visits Al Faw, one of Saddam

Hussein’s former palaces

In Baghdad, Tsuda was tasked with helping keep secure the largest coalition military facility in Baghdad - and the most populated in Iraq - Victory Base Complex, at the center of which sits Baghdad International Airport. “It’s like trying to secure a city,” he says of his role as assistant force protection officer of the complex. “You have people going in and out constantly.”

He was attached to Dragon Brigade, 18th Airborne Corps out of Fort Bragg, N.C., and says he was lucky to have a boss that encouraged officers to leave the base when they could to keep abreast of goings-on in the surrounding area. Because of that, he experienced everything from leading a nighttime search of homes to writing policy to tending to what he calls the “hey, you” missions. “Everytime something was wrong, (the brigade commander) asked me to go check it out,” Tsuda says. “It could be a breach in the perimeter wall, maybe someone found a bad guy in the base.”

Tsuda joined the National Guard in 1989 looking for a challenge and a college tuition waiver, and he expected someday he would go to war. He didn’t expect it would happen this late in his career. But late in his career worked well. To do his job, “I used every life experience I had.”

Derek Chow, 43 Army Corps of Engineers Tikrit, Iraq

The three things Derek Chow missed most during his four months in Iraq were his daughter Erin, sushi and surfing. He got two of the three in his first hours back: A sushi meal with Erin and his parents “right from the airport.”

Chow, a senior project manager with the Army Corps of Engineers Honolulu District, calls his wartime experience “very positive and worthwhile” and counts his greatest accomplishment as establishing a program to train Iraqi engineers on the corps’project and construction management process. It’s “a tried and true method for ensuring the delivery of quality products,” he writes in an e-mail interview from Tokyo, where he was on business for the corps.

Chow served as resident engineer for the corps’Danger Resident Office on Forward Operating Base Danger in Tikrit. The office managed and oversaw school repairs, railroad station and fire station rehabilitation and road construction, among other projects.

As Chow can attest, wartime dangers are real even in noncombatant roles. Recalling how a Humvee (HMMV) in his convoy was hit by a bomber, Chow writes: “I remember it well. It was on my daughter’s birthday, 22 May 05 at about 3 p.m. in the town of Bayji. We were driving fast and everyone was alert as usual. I was in the lead HMMV. All of a sudden, we heard a loud explosion and immediately, the sergeant in the third HMMV yelled over the radio, ‘We’ve been hit. We’ve been hit.’ Gary Wageman of my staff was in the third HMMV. We stopped immediately to go back and assist as the HMMV was disabled ... We decided to locate the person detonating the bomb ... searched houses on one side of the road, then the other, for the vehicle fleeing the scene. ... We flushed the detonator out, and the second HMMV providing security at the road saw, shot and killed him. We were called back to inspect the car, but before getting to it, another vehicle pulled out the body and took off. All that was left was blood in the car.”

He felt fear, he says, but it’s anger that “drives you in those situations.” Asked how he dealt with the low times in war, he says: “I saw and felt the dedication of the soldiers whom I believe had a tougher job than I. They had no choice to be there. Most were young. I would say 20 to 23 years old. ... It’s the kids who are dying over there. We need to help them

Page 1 of 2 pages for this story 1 2 >

E-mail this story | Print this page | Comments (0) | Archive | RSS

Most Recent Comment(s):