No Try Fool Me!

Editor’s note: This story is adapted from the forthcoming book Japanese Eyes American Heart, Volume II: Voices from the Home Front in World War II Hawaii.

|

By Gail Miyasaki

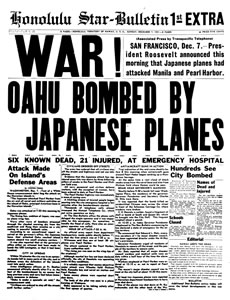

Seventy years ago, on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, at 7:55 a.m., Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in a surprise attack that shocked the United States and led to its entry into World War II. In Hawaii, the devastating attack cast suspicion on its Japanese residents, aliens and American citizens alike. In 1941, Hawaii’s Japanese were hard to miss, making up about 40 percent of the then territory’s population.

While much has been documented and justly celebrated about the valor and sacrifice of Hawaii’s 13,000 Nisei soldiers during World War II, less is known of the experiences of the vast majority of Japanese who lived through the bombing of Pearl Harbor by an enemy who looked like them. Two nisei, representing distinctly different experiences, share their personal recollections of Dec. 7, 1941, and wartime Hawaii as seen through local Japanese eyes:

Jane Komeiji was a 16-year-old high school student in 1941, living in Aala with two younger siblings and their widowed immigrant mother, a successful businesswoman active with the Japanese Buddhist temple. Now 86, Komeiji is a retired teacher, co-author of Okage Sama De: The Japanese in Hawaii, 18851985 (1986, updated 2008) and involved with the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii’s Historical Gallery Committee.

|

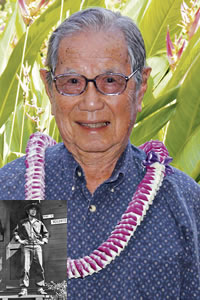

Ted Tsukiyama, in 1941 a 20-year-old University of Hawaii junior from Kaimuki, went on to volunteer for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the Military Intelligence Service in India and Burma. A Yale-educated attorney who marked a milestone 60 years as a lawyer in 2010 and is still an active arbitrator-mediator, Tsukiyama, now 90, is the historian for the Varsity Victory Volunteers, the 442nd and MIS in Hawaii.

Q: What was your experience on Dec. 7, 1941? What were your thoughts and feelings?

|

Komeiji: Disbelief. This boy blurted out that Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor and we were at war. I told him, “No try fool me!” The dark smoke in the sky must be a house on fire. Sunday school was canceled because of the attack, so I phoned Mother that I would come home right away. But when one of the boys, wanting to show off his new driver’s license, offered a ride to see the Pearl Harbor fire, I jumped into his car with others. From Kalihi, we had a clear view of “Battleship Row” engulfed in a long, wide curtain of black smoke. I was disappointed. Where were the roaring flames?

The drive home was through eerily quiet, empty streets and sidewalks. At Aala Park, there were no Sunday evangelists at the corner, no games of sipa sipa (Filipino wicker ball kicking game), no baseball games and no crowds at the bus stops. I caught “hell” when I got home, two hours late. I had never seen Mother so angry.

|

Fearful of the enemy’s return by air or sea, we stayed indoors as we were told, listening to the radio about the curfew and blackout from dusk to dawn. We slept in our street clothes, with flashlights, jackets and shoes laid out ready to grab and go. I could not sleep: What if the enemy landed on Oahu? Where could we hide? What if my family got separated? These worries kept repeating in my thoughts.

Tsukiyama: I had gone to the university junior prom the night before, so I wanted to sleep late, but was awakened by a constant rumbling. I saw the sky black with smoke and heard the KGU radio announcer screaming, “Take cover! Get off the streets! We are being attacked by Japanese planes! This is the real McCoy!”

I was stunned: “This can’t be happening!” I felt total shock, then numb with disbelief and denial. When I realized that we were being attacked by Japan, I felt a twinge of shame for being Japanese, followed by anguish and despair from an awful fore-

Page 1 of 2 pages for this story 1 2 >

E-mail this story | Print this page | Comments (0) | Archive | RSS

Most Recent Comment(s):