The Buddhist Way

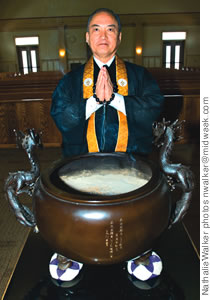

As Honpa Hongwanji Mission celebrates 120 years in Hawaii, Bishop Thomas Okano says it is modernizing and becoming more than just a Japanese organization. But one thing remains the same: the quest for human enlightenment

By Chad Pata

E-mail this story | Print this page | Archive | RSS |

Del.icio.us

Del.icio.us

In Honpa Hongwanji Mission’s 120th year in Hawaii, the goal remains the same: human enlightenment

As the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii celebrates its 120th anniversary in the Islands, it finds its duties evolving in the ever-flattening landscape of modern society.

What was once a bulwark for the local Japanese plantation population, providing recent immigrants comfort and peace in this foreign island community, is opening its doors to other cultures in order to perpetuate itself.

When Bishop Thomas Okano joined the church in 1967, all the services were still conducted in Japanese, as were the faces in the congregation. But as the immigrant population has morphed into a local population, changes were necessary to make the church remain viable.

“We cater still to the Japanese, but as the fourth and fifth generations arrive they are not Japanese-speaking at all,” says Okano. “Their name may be Tanaka or Nakamura, but they are English-speaking and American. Our biggest concern is to recruit and train more English-speaking ministers, otherwise we will not be able to reach these English-speaking members, not just Japanese but the population as a whole.”

While there are 36 temples in the state, there are only 30 ordained ministers, and some of the bigger urban temples, like the one on Pali Highway, retain five to serve their burgeoning congregation. This leaves ministers in rural areas having to serve three or four temples whose memberships are dwindling.

“The population that prefer Buddhism is not increasing in those rural areas,” says Okano.

“Though Buddhism is not just for Japanese, historically the orders came with the immigrants, so initially our duties were to serve Japanese-speaking, camp-centered immigrants, to help serve the Japanese culture, to continue on traditions.

|

“As the second generation emerged, they start going to school and away from camp and toward higher learning, so slowly the system eroded and plantations began to close, the children began to move to Honolulu. This is how there became a dispersment of population.”

Today they are finding ministers from all ethnic groups and backgrounds, including Filipinos and Native Americans. All the business of the church is conducted in English, even down to answering of phones, but these changes are not altering the core of the church.

“We are still mochi pounding on New Year’s Day and sipping sake,” says Bishop Okano. “We should not discard the good things, but we have to be open to new ideas. Our legislative session (among temples) used to be all bento for lunch.

Now one day we have bento, one day sandwich, so we’re changing!”

Adapting to shifting situations has been something Okano has been doing from a very young age. As a 4-year-old living in Pearl City with his parents and younger sister, he had a happy life as the son of Ryoshin Okano, minister of the Pearl City Hongwanji.

|

That all changed that fateful morning in December 1941 when he stood outside his home and watched those

Mitsubishi A6M Zeros come pouring over the mountains toward his home.

“I remember seeing the Japanese planes, looking at the planes and waving at them,” recalls Okano, “and some of them, my mother said, waved back.”

His father was rounded up that very afternoon, as he had been on the blacklist as a leader in the Japanese community.

“Lots of lifestyles of people changed after the attacks on Pearl Harbor,” says Okano. “People look at the Buddhist Church as the Japanese church, and anything to do with Japanese, well, there could be no more large assembly.”

His father was interned in Texas and his mother was given the choice to join him or to remain in Hawaii. Truth be told, it was not much of a choice at all. As a single mother with two young children and no means to support herself and no idea of how long the war would last or who would be the victor, she united her fate with her husband’s and submitted herself to the camp.

In 1943 the Okano family was selected to be exchanged for an American family that was interned in Japan. The swap took place in the picturesque city of Goa, India, and while free might not be the right word, the Okanos were released from behind the barbed wire fence for the first time in 24 months.

Being a Buddhist priest, the Japanese ordered Ryoshin Okano to become a navy chaplain for the troops in Singapore. As the war began to turn for the Americans, the Japanese began pulling back from their distant outposts to return home. The elder Okano was given permission to take himself and his first-born son home aboard a Red Cross relief ship named the Awa Maru.

But once aboard, they were ordered back off the ship by members of the Japanese army who commandeered it to bring back

Page 1 of 2 pages for this story 1 2 >

E-mail this story | Print this page | Comments (0) | Archive | RSS

Most Recent Comment(s):